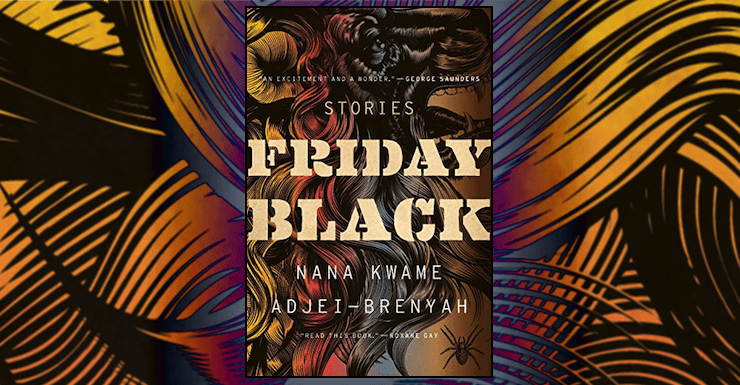

Friday Black is the debut collection of Syracuse-based writer Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, gathering twelve pieces of short fiction spanning from 2014 to now. These stories mingle the mundane and the extraordinary, the exaggerated and the surreal, all for the purpose of commenting on pivotal, often horrible moments in contemporary American culture. The collection is cutting from start to finish, a deep stare into the sociocultural abyss shot through with bleak humor.

From a gruesome timeloop tale whose protagonists are children to a metafictional riff on the danger of creating lives via prose, Adjei-Brenyah prods at tropes and expectations to create affective and moving stories exploring, above all, the “violence, injustice, and painful absurdities that black men and women contend with every day in this country.” It’s a haunting, unforgiving debut that pushes at genre boundaries in the service of art and criticism.

This is a challenging collection of stories that digs into the affective problem of “business as always” then uses that ennui to examine how far American culture would let things go, especially with regard to racism and anti-blackness. By pushing current events three small steps further, Adjei-Brenyah creates sweeps of dystopic horror that don’t appear much different from the present moment at all. Nothing in Friday Black feels impossible or unreal; in fact, the punch of the constant violence is that it’s utterly plausible despite the purposeful edginess of literary surrealism. Issues of authority, power, and social violence are dealt with as sticky webs, hideous and interrelated, whose effects are all-encompassing and inescapable.

And it does, in this case, feel relevant for me to point out the relation between text and reviewer before continuing. Namely, most of the stories collected in Friday Black are visceral, often-brutal explorations of contemporary black American experience and I do not want to approach claiming, as a white reader, to have access to or critical angles on that experience. The engagement I have with the collection is necessarily from the subject position I occupy, and while that is a given for any text, it seems particularly relevant to note given the politics of race, violence, and class Adjei-Brenyah is dealing with—as a matter of respect, if nothing else.

One of the most powerful and nauseating stories of the collection, “The Finkelstein 5,” comes first—and it’s a stellar example of Adjei-Brenyah’s critical lens, the raw horror that he distills from contemporary experience. The background of the story is that a man, “George Wilson Dunn,” murdered five black children outside a library with a chainsaw and the courts let him off scot free. The protagonist’s community is left to respond in complex, messy ways to their ongoing trauma as it manifests in every aspect of life within a culture that condones and encourages anti-black violence. This search for a functional or even survivable reaction forms the emotion core of the piece.

It is, I assume, no accident that read aloud the name George Wilson Dunn sounds like George Zimmerman (whose public and unpunished murder of a black teenager also figures in another piece, “Zimmer Land”). The defense attorney spouts a screed about “freedom” while the prosecutor is trying simply to argue that an adult man chased down and decapitated a seven-year-old girl—but the jury decides he was within his rights to do so. As the defense attorney says, “My client, Mister George Dunn, believed he was in danger. And you know what, if you believe something, anything, then that’s what matters most. Believing. In America we have the freedom to believe.” These courtroom scenes are interspersed throughout the story as the protagonist tries to navigate the world in constant awareness of his Blackness on a scale of one to ten—voice, clothes, stance, skin tone, location, activities—in the course of a normal day that does not, ultimately, remain normal. Adjei-Brenyah explores in brutal detail the internal conflict of a person, a community, suffering continual abuse and what possible responses even exist after a certain event horizon has been crossed. There are no simple answers, but there is pain, and fear, and anger. It’s a powerful story.

Commodification also features prominently as a form of social violence in several stories: the commodification of bodies, the corrosive consumption of late-stage capitalism, the entertainment value of trauma and oppression. Multiple stories are set in retail job environments, such as the titular piece, a mashup of zombie horror and the devaluation of human life in the face of material goods. Given contemporary treatment of the American worker, very little about these stories feels absurdist or satirical, despite the fact that there are trashbins for bodies in the shopping mall. As with all of the stories in the collection, it’s so close to the real monstrosity people wade through every day that the horror comes from the places where we can’t see the seams in the costume, where as a reader I’m aware it’s creative exaggeration but the emotional truth feels identical to the real.

Friday Black is also a collection of stories that primarily encompasses men’s experience, doing so with a level of emotional intimacy between the reader and the various protagonists that I appreciated. These are men and boys struggling to survive in an inhospitable world… who are nonetheless still men participating in patriarchy in a loop of complex inter-relational power, which Adjei-Brenyah doesn’t forget. Though women are less prominent in Friday Black, he is pointed in his representation of how his male protagonists do interact with them. For example, the protagonist of “Lark Street” struggles to deal with his girlfriend’s abortion—as described through a grisly fantastical plot device—but ultimately the narrative makes it clear that she is the one struggling most and he has a right to his emotions, but not at the cost of her emotional work.

Buy the Book

Friday Black

However, the corollary to Adjei-Brenyah’s facility at exploring men’s interiority is that women do appear primarily as set-dressings rather than as fully developed characters. Meaningful interaction occurs, for the most part, among men. One of the weakest pieces is “In Retail,” a companion story set in the same shopping mall store as “Friday Black” and “How to Sell a Jacket as Told by IceKing”—and it does read as a companion rather than a story that exists individually. It’s also one of the only stories from a woman’s point of view, aside from “Through the Flash.” The protagonist’s viewpoint feels underdeveloped and underexplored, a quick tidbit that offers the counterpoint to “How to Sell a Jacket as Told by IceKing” rather than a whole tale of its own.

Of course, one book can’t do all the work in the world simultaneously—and the perspective Adjei-Brenyah is offering on black masculinities in America is vital and significant. He is also working with a set of literary tropes (and a style of edge-pushing short fiction in particular) that are reminiscent of Chuck Palahniuk as much as anything. So, on the whole, the collection is multifaceted, provocative, and focused first on affect. His willingness to explore ethical and emotional complexity, offering incisive portrayals and few simple answers, gives Friday Black the kind of heft I don’t see often in short fiction debuts. I almost regret reading the book in one fell swoop, as these stories are all emotionally intense; I suspect taking it one at a time, letting each story settle individually, would’ve been a more productive approach given the content. It’s certainly an important book for our contemporary political moment.

Friday Black is available from Mariner Books.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.